لفرق بين الجوج ڤيرسيونات ديال: "لفلسفة"

لا ملخص تعديل |

ص Bot: Formatting ISBN |

||

| سطر 4: | سطر 4: | ||

'''لفلسفة''' (جات من φιλοσοφία ب ليونانية، وكاتقرا philosophia، وكاتعني حب لحكمة) <ref>"Strong's Greek: 5385. φιλοσοφία (philosophia) -- the love or pursuit of wisdom". ''biblehub.com''.</ref> هي دراسة ديال لأسئلة لأساسية ديال [[لوجود]]، [[لمعرفة]]، [[لأخلاق]]، [[لمنطق]]، [[لعقل]]، و [[لوغة]].<ref>"Philosophy". ''Lexico''. University of Oxford Press. 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref><ref>Sellars, Wilfrid (1963). ''Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind'' (PDF). Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. 1, 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref> هاد لأسئلة غالبا كاتكون على شكل [[معضلة|دي پروبليم]] <ref>Chalmers, David J. (1995). "Facing up to the problem of consciousness". ''Journal of Consciousness Studies''. '''2''' (3): 200, 219. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref><ref>Henderson, Leah (2019). "The problem of induction". ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref> لي خاصك تحلهم. أول واحد لي يمكن ستعمل لمصطلح ديال فلسفة هو [[ڤيتاغورس]] (لي عاش تقريبا ما بين 570 و 475 قبل لميلاد). |

'''لفلسفة''' (جات من φιλοσοφία ب ليونانية، وكاتقرا philosophia، وكاتعني حب لحكمة) <ref>"Strong's Greek: 5385. φιλοσοφία (philosophia) -- the love or pursuit of wisdom". ''biblehub.com''.</ref> هي دراسة ديال لأسئلة لأساسية ديال [[لوجود]]، [[لمعرفة]]، [[لأخلاق]]، [[لمنطق]]، [[لعقل]]، و [[لوغة]].<ref>"Philosophy". ''Lexico''. University of Oxford Press. 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref><ref>Sellars, Wilfrid (1963). ''Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind'' (PDF). Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. 1, 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref> هاد لأسئلة غالبا كاتكون على شكل [[معضلة|دي پروبليم]] <ref>Chalmers, David J. (1995). "Facing up to the problem of consciousness". ''Journal of Consciousness Studies''. '''2''' (3): 200, 219. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref><ref>Henderson, Leah (2019). "The problem of induction". ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. Retrieved 28 March 2019.</ref> لي خاصك تحلهم. أول واحد لي يمكن ستعمل لمصطلح ديال فلسفة هو [[ڤيتاغورس]] (لي عاش تقريبا ما بين 570 و 475 قبل لميلاد). |

||

[[لمناهج ديال لفلسفة]] فيها [[لإستجواب سقراطي]]، [[لمنهج سقراطي]]، [[ديالكتيك]]، و تقديم لمنهجي. <ref>Adler, Mortimer J. (2000). ''How to Think About the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization''. Chicago, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN <bdi>978-0-8126-9412-3</bdi>.</ref><ref>Quinton, Anthony. 1995. "The Ethics of Philosophical Practice." P. 666 in ''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', edited by T. Honderich. New York: Oxford University Press. |

[[لمناهج ديال لفلسفة]] فيها [[لإستجواب سقراطي]]، [[لمنهج سقراطي]]، [[ديالكتيك]]، و تقديم لمنهجي. <ref>Adler, Mortimer J. (2000). ''How to Think About the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization''. Chicago, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN <bdi>978-0-8126-9412-3</bdi>.</ref><ref>Quinton, Anthony. 1995. "The Ethics of Philosophical Practice." P. 666 in ''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', edited by T. Honderich. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0.↵↵"Philosophy is rationally critical thinking, of a more or less systematic kind about the general nature of the world (metaphysics or theory of existence), the justification of belief (epistemology or theory of knowledge), and the conduct of life (ethics or theory of value). Each of the three elements in this list has a non-philosophical counterpart, from which it is distinguished by its explicitly rational and critical way of proceeding and by its systematic nature. Everyone has some general conception of the nature of the world in which they live and of their place in it. Metaphysics replaces the unargued assumptions embodied in such a conception with a rational and organized body of beliefs about the world as a whole. Everyone has occasion to doubt and question beliefs, their own or those of others, with more or less success and without any theory of what they are doing. Epistemology seeks by argument to make explicit the rules of correct belief formation. Everyone governs their conduct by directing it to desired or valued ends. Ethics, or moral philosophy, in its most inclusive sense, seeks to articulate, in rationally systematic form, the rules or principles involved." (p. 666).</ref> |

||

لأسئلة لفلسفية لكلاسيكية ممكن تكون شي حاجة بحال: "واش ممكن نعرفو؟" ايلا كان لجواب اه "واش ممكن نتأكدو؟"<ref>Greco, John, ed. (2011). ''The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism'' (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN <bdi>978-0-19-983680-2</bdi>.</ref><ref>Glymour, Clark (2015). "Chapters 1–6". ''Thinking Things Through: An Introduction to Philosophical Issues and Achievements'' (2nd ed.). A Bradford Book. ISBN <bdi>978-0-262-52720-0</bdi>.</ref><ref>Pritchard, Duncan. "Contemporary Skepticism". ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 25 April 2016.</ref> |

لأسئلة لفلسفية لكلاسيكية ممكن تكون شي حاجة بحال: "واش ممكن نعرفو؟" ايلا كان لجواب اه "واش ممكن نتأكدو؟"<ref>Greco, John, ed. (2011). ''The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism'' (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN <bdi>978-0-19-983680-2</bdi>.</ref><ref>Glymour, Clark (2015). "Chapters 1–6". ''Thinking Things Through: An Introduction to Philosophical Issues and Achievements'' (2nd ed.). A Bradford Book. ISBN <bdi>978-0-262-52720-0</bdi>.</ref><ref>Pritchard, Duncan. "Contemporary Skepticism". ''Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 25 April 2016.</ref> |

||

| سطر 44: | سطر 44: | ||

==== لفلسفة لمعاصرة ==== |

==== لفلسفة لمعاصرة ==== |

||

[[لفلسفة لمعاصرة]] بدات كاتبان ف لعالم لغربي مع مفكرين بحال [[طوماص هوبس]] و [[روني ديكارط|ريني ديكارط]] (1596-1650). مع تقدم ديال لعلوم طبيعية، لفلسفة لمعاصرة هتمّات ب أنها تطور واحد لأساس منطقي و علماني ديال لمعرفة، وتبعد من لبنيات تقليدية ديال سلطة، بحال [[دين]]، [[لفلسفة لمدرسية]]، و [[كنيسة|لكنيسة]]. من أكبر لفلاسفة لمعاصرين لمعروفين كاين: [[باروخ سپينوزا|سپينوزا]]، [[لايبنيتس]]، [[جون لوك|لوك]]، [[ديفيد هيوم|هيوم]]، و [[ايمانويل كانط|كانط]].<ref>Rutherford, Donald. 2006. ''The Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Philosophy''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. |

[[لفلسفة لمعاصرة]] بدات كاتبان ف لعالم لغربي مع مفكرين بحال [[طوماص هوبس]] و [[روني ديكارط|ريني ديكارط]] (1596-1650). مع تقدم ديال لعلوم طبيعية، لفلسفة لمعاصرة هتمّات ب أنها تطور واحد لأساس منطقي و علماني ديال لمعرفة، وتبعد من لبنيات تقليدية ديال سلطة، بحال [[دين]]، [[لفلسفة لمدرسية]]، و [[كنيسة|لكنيسة]]. من أكبر لفلاسفة لمعاصرين لمعروفين كاين: [[باروخ سپينوزا|سپينوزا]]، [[لايبنيتس]]، [[جون لوك|لوك]]، [[ديفيد هيوم|هيوم]]، و [[ايمانويل كانط|كانط]].<ref>Rutherford, Donald. 2006. ''The Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Philosophy''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82242-8. "Most often this [period] has been associated with the achievements of a handful of great thinkers: the so-called 'rationalists' (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) and 'empiricists' (Locke, Berkeley, Hume), whose inquiries culminate in Kant's 'Critical philosophy.' These canonical figures have been celebrated for the depth and rigor of their treatments of perennial philosophical questions…" (p. 1).</ref><ref>Nadler, Steven. 2008. ''A Companion to Early Modern Philosophy''. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99883-0. "The study of early modern philosophy demands that we pay attention to a wide variety of questions and an expansive pantheon of thinkers: the traditional canonical figures (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume), to be sure, but also a large 'supporting cast'…" (p. 2).</ref><ref>Kuklick, Bruce. 1984. "Seven Thinkers and How They Grew: Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz; Locke, Berkeley, Hume; Kant." In ''Philosophy in History'', edited by Rorty, Schneewind, and Skinner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. "Literary, philosophical, and historical studies often rely on a notion of what is ''canonical''. In American philosophy scholars go from Jonathan Edwards to John Dewey; in American literature from James Fenimore Cooper to F. Scott Fitzgerald; in political theory from Plato to Hobbes and Locke.… The texts or authors who fill in the blanks from A to Z in these, and other intellectual traditions, constitute the canon, and there is an accompanying narrative that links text to text or author to author, a 'history of' American literature, economic thought, and so on. The most conventional of such histories are embodied in university courses and the textbooks that accompany them. This essay examines one such course, the History of Modern Philosophy, and the texts that helped to create it. If a philosopher in the United States were asked why the seven people in my title comprise Modern Philosophy, the initial response would be: they were the best, and there are historical and philosophical connections among them." (p. 125).</ref> |

||

لفلسفة ديال لقرن 19 تأنسپيرات من واحد لحركة لي كانت ف لقرن 18، ولي كاتسما "[[عصر لأنوار]]"، ولي كاتشمل فلاسفة بحال [[هيڭل]]، أشهر فيلسوف ديال [[لمتالية لألمانية]]، [[كيركڭارد]] لي ديڤالوپا لا باز ديال [[لوجودية]]، [[نيتش]] لي تشهر ب معاداة لمسيحية، [[دجون ستيوارت ميل]] لي روّج ل نفعية، و [[كارل ماركس]] لي طور لأسس ديال [[شيوعية]]. ف لقرن 20 وقعات واحد تفريقا بين لفلسفة تحليلية و لفلسفة لقارّية. و بانو بزاف ديال لمدارس فلسفية بحال [[لفينومينولوجيا]]، [[لوجودية]]، [[لوضعية لمنطقية]]، [[لبراڭماتية]]، و [[لإنعطاف لوغوي]]. |

لفلسفة ديال لقرن 19 تأنسپيرات من واحد لحركة لي كانت ف لقرن 18، ولي كاتسما "[[عصر لأنوار]]"، ولي كاتشمل فلاسفة بحال [[هيڭل]]، أشهر فيلسوف ديال [[لمتالية لألمانية]]، [[كيركڭارد]] لي ديڤالوپا لا باز ديال [[لوجودية]]، [[نيتش]] لي تشهر ب معاداة لمسيحية، [[دجون ستيوارت ميل]] لي روّج ل نفعية، و [[كارل ماركس]] لي طور لأسس ديال [[شيوعية]]. ف لقرن 20 وقعات واحد تفريقا بين لفلسفة تحليلية و لفلسفة لقارّية. و بانو بزاف ديال لمدارس فلسفية بحال [[لفينومينولوجيا]]، [[لوجودية]]، [[لوضعية لمنطقية]]، [[لبراڭماتية]]، و [[لإنعطاف لوغوي]]. |

||

مراجعة 18:23، 13 شتنبر 2020

لفلسفة (جات من φιλοσοφία ب ليونانية، وكاتقرا philosophia، وكاتعني حب لحكمة) [1] هي دراسة ديال لأسئلة لأساسية ديال لوجود، لمعرفة، لأخلاق، لمنطق، لعقل، و لوغة.[2][3] هاد لأسئلة غالبا كاتكون على شكل دي پروبليم [4][5] لي خاصك تحلهم. أول واحد لي يمكن ستعمل لمصطلح ديال فلسفة هو ڤيتاغورس (لي عاش تقريبا ما بين 570 و 475 قبل لميلاد).

لمناهج ديال لفلسفة فيها لإستجواب سقراطي، لمنهج سقراطي، ديالكتيك، و تقديم لمنهجي. [6][7]

لأسئلة لفلسفية لكلاسيكية ممكن تكون شي حاجة بحال: "واش ممكن نعرفو؟" ايلا كان لجواب اه "واش ممكن نتأكدو؟"[8][9][10]

لفلاسفة كايطرحو بزاف ديال لأسئلة لخرا لي متعلقة ب لواقع، متلا: "واش كاينا شي طريقة لي باش نعيشو لماكسيموم د لحياة؟"، "واش ممكن تسما انسان مزيان ايلا قدرتي دير حاجة خايبة بلا ما يعرف تا شي واحد؟"، "واش ناس عندهم حرية لإرادة؟".

شحال هادي، لفلسفة كانت كاتشمل ڭاع لأنواع ديال لمعرفة. [11] من أرسطو حتال لقرن 19، كانت لفلسفة طبيعية فيها علم لفلك، طب، و لفيزيك. متلا، اسحاق نيوتن كتب واحد لكتاب ف 1687 سميتو لمبادئ رياضية د لفلسفة طبيعية. هاد لكتاب من بعد تكلاسا مع لكتوبا د لفيزيك. ف لقرن 19، فاش ولاّ رّوشرش سيونتيفيك كتير فهاد لفروع ديال لفلسفة، بدات هاد لفروع كاتخصص، وشوية شوية بدات كاتنفاصل من لفلسفة. [12][13] ليوم، تخصصات بحال لبسيكولوجي، سوسيولوجي، لسانيات، و ليكونومي، ولاو كولهم مستقلين على لفلسفة. من جهة خرا، كاينين شي نخصصات لي مازال قراب من لفلسفة، بحال لعلم، لفن، و سياسة. متلا، واش لجمال داتي ولا موضوعي؟[14][15] واش كاينين بزاف ديال لمناهج لعلمية ولا غير واحد؟[16] واش ليوتوپيا شي حاجة ممكنة ولا غير خيال ما يمكنش يتحقق؟

مقدمة

لمعرفة

مبدئيا، كلمة فلسفة كاتشير لأي مجموعة من لمعارف[17] بهاد لمعنى، لفلسفة قريبة ل دين، لماط، لعلوم طبيعية، تعليم، و سياسة.

تطور ديال لفلسفة

بزاف ديال لمناضرات لفلسفية لي بدات ف قديم زمان مازال كاتعاود ليوم. لفيلسوف نڭليزي كولين ماكڭن (1933) تايڭول بلي ما وقع حتا شي تقدم فلسفي فهاد لمدة كاملة.[18] لفيلسوف لأسترالي ديفيد تشالمرز (2013) من جهة خرا تيشوف بلي لفلسفة تقدمات بنفس لوتيرة ديال تقدم ديال لعلم.[19] فلاسفة خرين بحال بروور (2011) تايڭولو بلي لمقياس ديال تقدم أصلا ماشي صحيح باش نحكمو بيه على نشاط لفلسفي. [20]

نضرة تاريخية

بمعنى عام، لفلسفة مرتابطة ب لحكمة، تقافة، و لبحت على لمعرفة. بهاد لمعنى، ڭاع تقافات و لمجتمعات كايسولو أسئلة فلسفية، بحال: "كيفاش نقدرو نعيشو؟" و "شنو هي طبيعة ديال لحقيقة؟".

لفلسفة لغربية

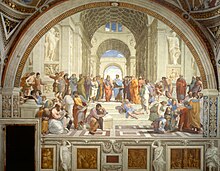

لفلسفة لغربية هي تقاليد لفلسفية ديال لعالم لغربي. تاريخ ديالها كايرجع ل عهد لفلاسفة لي قبل سقراط، لي كانو أكتيڤ ف ليونان ف لقرن 6 قبل لميلاد، بحال طاليس و ڤيتاغورس.

لفلسفة لغربية ممكن تقسم ل 3 د لأنواع

- لفلسفة لقديمة: ديال رومان و ليونان

- لفلسفة ديال لعصور لوسطى: لي مبازيا على لمسيحية

- لفلسفة لمعاصرة

لفترة لقديمة

لمعرفة ديالنا ب لعصور لقديمة بدات معا طاليس ف لقرن 6 قبل لميلاد، واخا لمعرفة ديالنا عموما ب لفلاسفة لي قبل سقراط قليلة. لفترة لقديمة كانت محكومة من لفلاسفة ديال ليونان، لي كانو تأنسپيراو بزاف من لأفكار ديال سقراط. واحد من هاد لفلاسفة لي معروفين هو أفلاطون، لي دار لأكاديمية، و تلميد ديالو أرسطو [21]لي دار لمدرسة لمشّائية. كانو مدارس فلسفية خرا بحال تشاؤمية، رّواقية، شكوكية، و لأبيقورية.

لمواضيع لي كانو كايناقشوها ليونان كانت متنوعة: متلا، لميتافيزيكس، علم لفلك، لمنطق و لمعرفة.

مع صعود ديال لإمبراطورية رومانية، حتى لفلسفة ليونانية ولا عندها دور كبير عند لفلاسفة رومان بحال سيسيرو و سينيكا.

لفترة ديال لعصور لوسطى

لفلسفة ديال لعصور لوسطى (بين لقرن 15 و 16) هي لفترة لي جات بعدما طاحت لإمبراطورية رومانية لغربية، و لي بدات كاتنتاشر فيها لمسيحية بقوة، ولكن بقا واحد شوية ديال لأفكار ليونانية و رومانية. دي پروبليم بحال لوجود، طبيعة ديال الله، طبيعة ديال لإيمان و لمنطق، لميتافيزيكس، و معضلة شر كانو كايتناقشو ف ديك لوقت. بعض لمفكرين لي كانو فديك لوقت سان أوڭستين، طوما لأكويني، روجر باكون، و بوطيوس. هاد لفلاسفة كانو كيعتابرو لفلسفة ديالهم واحد لحاجة لي كاتعاون لإيمان (ancilla theologiae)، و ب تالي حاولو أنهم يوفقو ما بين لفلسفة و تأويل ديالهم ل نص ديني. هاد لفترة عرفات تطور ديال لفلسفة لمدرسية، لي هي واحد لميطود كاتقرّا ف لجامعات، وكاتستعمل لمناهج دينية لمسيحية ف تحليل نقدي. فعصر نهضة، بداو ناس كايرجعو ل نصوص لاتينية و رومانية لقديمة، و بانت لفلسفة لإنسانية.

لفلسفة لمعاصرة

لفلسفة لمعاصرة بدات كاتبان ف لعالم لغربي مع مفكرين بحال طوماص هوبس و ريني ديكارط (1596-1650). مع تقدم ديال لعلوم طبيعية، لفلسفة لمعاصرة هتمّات ب أنها تطور واحد لأساس منطقي و علماني ديال لمعرفة، وتبعد من لبنيات تقليدية ديال سلطة، بحال دين، لفلسفة لمدرسية، و لكنيسة. من أكبر لفلاسفة لمعاصرين لمعروفين كاين: سپينوزا، لايبنيتس، لوك، هيوم، و كانط.[22][23][24]

لفلسفة ديال لقرن 19 تأنسپيرات من واحد لحركة لي كانت ف لقرن 18، ولي كاتسما "عصر لأنوار"، ولي كاتشمل فلاسفة بحال هيڭل، أشهر فيلسوف ديال لمتالية لألمانية، كيركڭارد لي ديڤالوپا لا باز ديال لوجودية، نيتش لي تشهر ب معاداة لمسيحية، دجون ستيوارت ميل لي روّج ل نفعية، و كارل ماركس لي طور لأسس ديال شيوعية. ف لقرن 20 وقعات واحد تفريقا بين لفلسفة تحليلية و لفلسفة لقارّية. و بانو بزاف ديال لمدارس فلسفية بحال لفينومينولوجيا، لوجودية، لوضعية لمنطقية، لبراڭماتية، و لإنعطاف لوغوي.

لفلسفة ديال شرق لأوسط

لمنطقة ديال لهلال لخصيب، إيران و لمنطقة لعربية كانو مناطق لي بانت فيهم لفلسفة فوقت مبكر. وليوم هاد لمناطق كاملة محكومة ب تقافة لإسلامية. أول نوع ديال لفلسفة لي بان فمنطقة لهلال لحصيب كان متعلق ب شخص وتصرفات ديالو، وكيفا يقدر لواحد يتصرف بطريقة أخلاقية. هادشي نتاشر عبر حجّايات و أساطير و حكم. ف مصر لقديمة، هاد نصوص كانو معروفين ب "sebyat" لي كاتعني تعاليم. هاد تعاليم هوما لي خلاونا نفهمو لفلسفة لمصرية لقديمة. علم لفلك لبابلي حتا هو هضر على بزاف د لإفترضات فلسفية على لكون، ولي كان عندها تأتير على ليونان لقديمة. لفلسفة ليهودية و لمسيحية هوما فلسفات دينية لي بانت ف شرق لأوسط و أوروبا، ولي بجوج كايتشاركو ف مراجع قديمة بحال تاناخ و توحيد. لفلسفة لإيرانية قبل لإسلام بدات مع زرادشت، لي كان واحد من لولين لي هضرو على توحيد، وتنائية ديال لخير وشر. هاد لأفكار هي لي تأنسپيراو منها ديانات خرا بحال لمانوية، لمزدكية، و زورانية. بعد لغزوات لإسلامية، لفلسفة لإسلامية لقديمة طورات لفلسفة ليونانية بشكل جديد. لعصر دهبي ل لإسلام كان عندو تأتير على تطور تقافي ف أوروپا. لفلاسفة لي عاشو ف ديك لوقت بحال لكندي (لقرن 9) ، ابن سينا (980-1037)، و ابن رشد (لقرن 12) تأترو ب أرسطو. فلاسفة خرين بحال لغزالي كانو ضد أرسطو و لمناهج ديالو. لفلاسفة ديال ديك لوقت قدرو يطورو لمنهج تجريبي نضرية ديال لبصريات، و لفلسفة ديال لقانون. ابن خلدون كان واحد من أهم لفلاسفة ديال تاريخ فديك لوقت. ف إيران، عداد من لمدارس لفلسفية لإسلامية ستامرّات ف لخدمة ديالها، واخّا سالا لعصر دهبي ديال لإسلام. ف لقرن 19 و 20 بانت واحد "نهضة" ف لعالم ناطق ب لعربية، ولي أترات على لفكر لإسلامي ديال ليوم.

لفلسفة لهندية

لفلسفة لهندية كاتشمل بزاف د تقاليد لفلسفية لي بانت ف لقارة لهندية من لقديم، لجينية و لبودية بانو ف لخّر ديال لفترة لڤيدية، و لهندوسية بانت من بعد واحد لمرحلة ديال لإندماج ديال بزّاف ديال تقاليد.

لفلسفة لجينية

لفلسفة لبودية

لفلسفة لهندوسية

لفلسفة لإفريقية

لمصادر

- ^ "Strong's Greek: 5385. φιλοσοφία (philosophia) -- the love or pursuit of wisdom". biblehub.com.

- ^ "Philosophy". Lexico. University of Oxford Press. 2020. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Sellars, Wilfrid (1963). Empiricism and the Philosophy of Mind (PDF). Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd. pp. 1, 40. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Chalmers, David J. (1995). "Facing up to the problem of consciousness". Journal of Consciousness Studies. 2 (3): 200, 219. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Henderson, Leah (2019). "The problem of induction". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 28 March 2019.

- ^ Adler, Mortimer J. (2000). How to Think About the Great Ideas: From the Great Books of Western Civilization. Chicago, Ill.: Open Court. ISBN 978-0-8126-9412-3.

- ^ Quinton, Anthony. 1995. "The Ethics of Philosophical Practice." P. 666 in The Oxford Companion to Philosophy, edited by T. Honderich. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-866132-0.↵↵"Philosophy is rationally critical thinking, of a more or less systematic kind about the general nature of the world (metaphysics or theory of existence), the justification of belief (epistemology or theory of knowledge), and the conduct of life (ethics or theory of value). Each of the three elements in this list has a non-philosophical counterpart, from which it is distinguished by its explicitly rational and critical way of proceeding and by its systematic nature. Everyone has some general conception of the nature of the world in which they live and of their place in it. Metaphysics replaces the unargued assumptions embodied in such a conception with a rational and organized body of beliefs about the world as a whole. Everyone has occasion to doubt and question beliefs, their own or those of others, with more or less success and without any theory of what they are doing. Epistemology seeks by argument to make explicit the rules of correct belief formation. Everyone governs their conduct by directing it to desired or valued ends. Ethics, or moral philosophy, in its most inclusive sense, seeks to articulate, in rationally systematic form, the rules or principles involved." (p. 666).

- ^ Greco, John, ed. (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Skepticism (1st ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983680-2.

- ^ Glymour, Clark (2015). "Chapters 1–6". Thinking Things Through: An Introduction to Philosophical Issues and Achievements (2nd ed.). A Bradford Book. ISBN 978-0-262-52720-0.

- ^ Pritchard, Duncan. "Contemporary Skepticism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ "The English word "philosophy" is first attested to c. 1300, meaning "knowledge, body of knowledge."↵↵Harper, Douglas. 2020. "philosophy (n.)." Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Shapin, Steven (1998). The Scientific Revolution (1st ed.). University Of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-75021-7.

- ^ Briggle, Robert, and Adam Frodeman (11 January 2016). "When Philosophy Lost Its Way | The Opinionator". New York Times. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ^ Sartwell, Crispin (2014). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Beauty (Spring 2014 ed.).

- ^ "Plato, Hippias Major | Loeb Classical Library". Loeb Classical Library. Retrieved 27 April 2016.

- ^ Feyerabend, Paul; Hacking, Ian (2010). Against Method (4th ed.). Verso. ISBN 978-1-84467-442-8.

- ^ "The English word "philosophy" is first attested to c. 1300, meaning "knowledge, body of knowledge."↵↵Harper, Douglas. 2020. "philosophy (n.)." Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ McGinn, Colin (1993). Problems in Philosophy: The Limits of Inquiry (1st ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-55786-475-8.

- ^ Chalmers, David. 7 May 2013. "Why isn't there more progress in philosophy?" [video lecture]. Moral Sciences Club. Faculty of Philosophy, University of Cambridge. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- ^ Brewer, Talbot (2011). The Retrieval of Ethics (1st ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-969222-4.

- ^ Process and Reality p. 39

- ^ Rutherford, Donald. 2006. The Cambridge Companion to Early Modern Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82242-8. "Most often this [period] has been associated with the achievements of a handful of great thinkers: the so-called 'rationalists' (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz) and 'empiricists' (Locke, Berkeley, Hume), whose inquiries culminate in Kant's 'Critical philosophy.' These canonical figures have been celebrated for the depth and rigor of their treatments of perennial philosophical questions…" (p. 1).

- ^ Nadler, Steven. 2008. A Companion to Early Modern Philosophy. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-99883-0. "The study of early modern philosophy demands that we pay attention to a wide variety of questions and an expansive pantheon of thinkers: the traditional canonical figures (Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume), to be sure, but also a large 'supporting cast'…" (p. 2).

- ^ Kuklick, Bruce. 1984. "Seven Thinkers and How They Grew: Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz; Locke, Berkeley, Hume; Kant." In Philosophy in History, edited by Rorty, Schneewind, and Skinner. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. "Literary, philosophical, and historical studies often rely on a notion of what is canonical. In American philosophy scholars go from Jonathan Edwards to John Dewey; in American literature from James Fenimore Cooper to F. Scott Fitzgerald; in political theory from Plato to Hobbes and Locke.… The texts or authors who fill in the blanks from A to Z in these, and other intellectual traditions, constitute the canon, and there is an accompanying narrative that links text to text or author to author, a 'history of' American literature, economic thought, and so on. The most conventional of such histories are embodied in university courses and the textbooks that accompany them. This essay examines one such course, the History of Modern Philosophy, and the texts that helped to create it. If a philosopher in the United States were asked why the seven people in my title comprise Modern Philosophy, the initial response would be: they were the best, and there are historical and philosophical connections among them." (p. 125).